Mayor Hancock’s Transportation Policy Is Failing to Achieve His Climate Goals

There's a huge gulf between what the mayor says he's doing to reduce transportation emissions, and what he's actually accomplished.

Chances are that when you pay your RTD fare or hop on your bike or walk to the grocery store, you’re not trying to save the planet. But by getting around without a car, you’re helping to curb global warming: Transportation is the second largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in Denver.

While Mayor Hancock says he’s committed to climate action, his transportation record says otherwise. The Hancock administration is failing to attain the goals for walking, biking, and transit laid out in its climate plans.

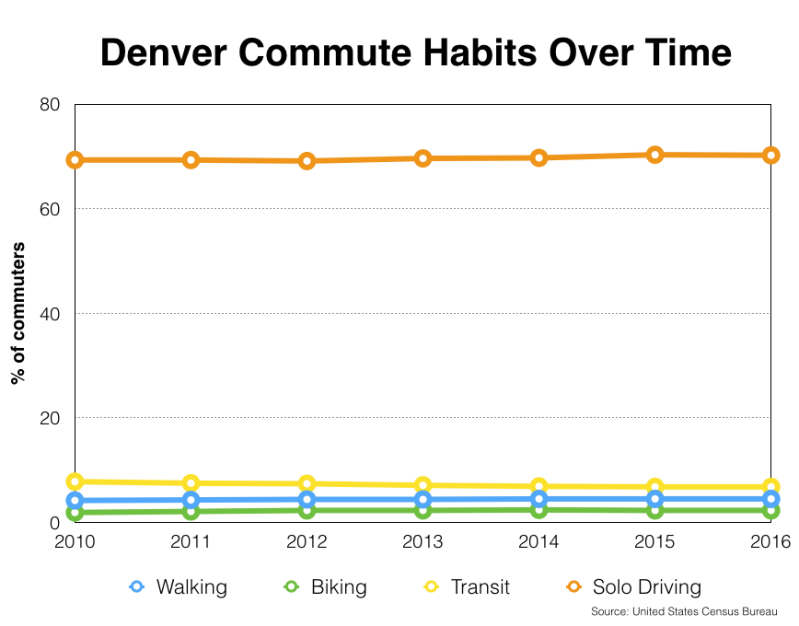

Hancock’s 2015 Climate Action Plan reiterated the city’s goal of cutting the rate of solo car commutes to 60 percent by 2020. Yet solo drivers still account for more than 70 percent of commutes, according to the U.S. Census, a rate that has barely budged since Hancock took office in 2011.

By 2020, the climate plan aims to bring Denver’s greenhouse gas emissions back to 1990 levels. And by 2050, the goal is to bring emission 80 percent below 2005 levels. The objectives are good, but the plan lacks concrete metrics and benchmarks, says Alana Miller, a Denver-based policy analyst at Frontier Group.

“Denver’s overall climate goals are definitely ambitious and laudable, and I think were we to meet those goals it puts us on track with where the international scientific community says we need to be,” Miller said. “The thing that seems to be missing… are the interim goals and some more concrete metrics around how we actually meet those goals.”

The climate plan lists strategies like “complete streets,” for example, but there’s no framework to ensure follow-through — and the city’s complete streets policy remains weak. Miller suggested aiming for a specific amount of bus lane mileage implemented by a certain date, and then regularly assessing progress toward that goal.

Hancock has produced nothing like that. And in the absence of a more detailed action plan, Denver is nowhere near the pace it needs to sustain to hit its 2020 climate goal.

Moving the goalposts

The same pattern is apparent in Hancock’s other citywide plans. The administration sets ambitious goals but doesn’t lay out a clear path to achieve them.

Hancock’s 2011 bike plan, known as “Denver Moves,” called for 15 percent of all commutes to be made by bike or by foot by 2020. At the time, the share of commutes by walking or biking was 6.4 percent. Today, with 18 months to go, walking and biking account for just 7 percent of commutes, according to the Census.

Denver Moves lays out the number of bikeway miles the city will build, but offers no timetable for implementation. Same goes for the city’s Pedestrians and Trails plan — there is no timetable.

“If Denver is serious about tackling its transportation emissions, the city has to reflect its values through infrastructure,” said Catherine Cox Blair, a Denver-based senior advisor with the Natural Resources Defense Council. “We want walking and biking to be safe, pleasant, everyday modes of travel, yet our streets are given over almost entirely to cars. Imagine what an incredible place Denver would be for everyone if we actually reflected our goals in our allocation of street space?”

Last year, Hancock moved the goalposts: He released a Mobility Action Plan that aims for 15 percent walking and biking mode share by 2030 — a full decade later than the original goal. By then, it will be up to another mayor to set Denver on a path toward sustainable transportation. Hancock will be term-limited out of office in 2023, if he’s re-elected next year.

The plan also laid out a transit mode share goal for the first time — 15 percent of commute trips by 2030, up from 7 percent today. But again, Hancock failed to provide a clear path to implementation. The plan lays out broad ideas like paying RTD to expand Denver transit service, but doesn’t say how much will be devoted to the new transit service, or when it will go live.

Leading Denver backward on climate by building more highways

Hancock fancies himself a climate mayor because he verbally committed Denver to the Paris climate accords. While he may have scored some political points in the wake of President Trump’s withdrawal from the accords, it carried the taint of hypocrisy.

Along with Governor Hickenlooper, Hancock was a key player enabling Colorado DOT to triple the footprint of a 10-mile stretch of I-70, which will pump more cars and trucks through the city.

“We’ve written a lot of reports around highway expansion and generally find that pumping a bunch of money into large highway projects actually induces demand, it causes more people to drive, and that creates more emissions,” says Miller. “These highway projects are super expensive, they can cost billions of dollars, and spending that amount of money not only diverts resources that would be better spent on low-carbon transportation options like transit and walking and biking, but it actually creates a built environment that encourages more driving and will for many decades to come.”

Denver’s climate plan clearly states: “Single-occupancy motorized vehicle travel is the most inefficient mode of transportation.” Yet the $2.2 billion I-70 expansion is going to produce a lot more single-occupancy motorized vehicle travel.

Electric cars aren’t enough

Widespread adoption of electric cars? There’s a plan for that. Hickenlooper has one, and Hancock is developing one.

Under Trump, the Environmental Protection Agency also has a plan: Weaken regulations on tailpipe pollution as much as possible.

So while Miller applauds Hickenlooper’s commitment to California-style emissions standards, the fact remains that moving more people in less space (by foot, bike, bus, and train) is the most efficient way for people to get around in cities.

“Obviously electrifying transportation will be really critical and any cars we have on the road should run on renewable energy, and that can do a lot to reduce emissions,” Miller says. “But it’s really going to take having fewer cars on the road.

“I think the good news is that we have the tools. A lot of these things aren’t even new things — transit’s been around for a century and walking and biking have been around for a long time. It’s tried and true.”