Denver’s sidewalks need a lot of help: Where do we start?

By Nicholas Coppola, MEng and Wes Marshall, PhD, PE

This guest commentary is by Nicholas Coppola, a PhD candidate, and Wes Marshall, a Professor of Civil Engineering with the University of Colorado Denver.

The future of transportation is littered with promises of driverless cars, hyperloops, and delivery drones. Yet, we live in a present where we can’t even get our sidewalks right.

Denver has long struggled with its sidewalks. And despite a major push with the Neighborhood Sidewalk Repair Program (NSRP), progress has been slow. A recent audit by the Denver Auditor’s office estimates that the program will take more than 50 years to complete at its current pace. Given the current level of sidewalk funding, 50 years is extremely optimistic .

Denver is a city with over 2,700 miles of roadway. Call 311 about a pothole? The city will fix it within 3 business days. If the weather is good, most are filled within 2 days.

Sidewalks are a different story. The NSRP won’t actually fix your broken sidewalk. Why? Well, the city puts that onus on the adjacent property owners. The NSRP program will point out the problem, and if you qualify, they will offer “extended repayment assistance and affordability discounts.” That is, once they get around to inspecting your neighborhood.

So how does a city like Denver take a more proactive approach to providing the most fundamental transportation infrastructure? Where should they start?

The obvious answer is to start where the sidewalks are missing or in the worst shape. But there are two issues with that idea. First, most cities have so many problematic areas that this strategy wouldn’t narrow things down all that much. Second, very few cities even systemically collect data on the state of their sidewalks to begin with.

So where else could we start?

Nationwide, more than one-quarter of all trips are less than one mile. According to the National Household Travel Survey (NHTS), people use a car for 60% of those trips that are one mile or less.

So what if we first figured out where these short driving trips are taking place? Wouldn’t focusing in on the parts of a city with a high percentage of short trips being made by automobile give us a better place to start when it comes to investing our sidewalk infrastructure?

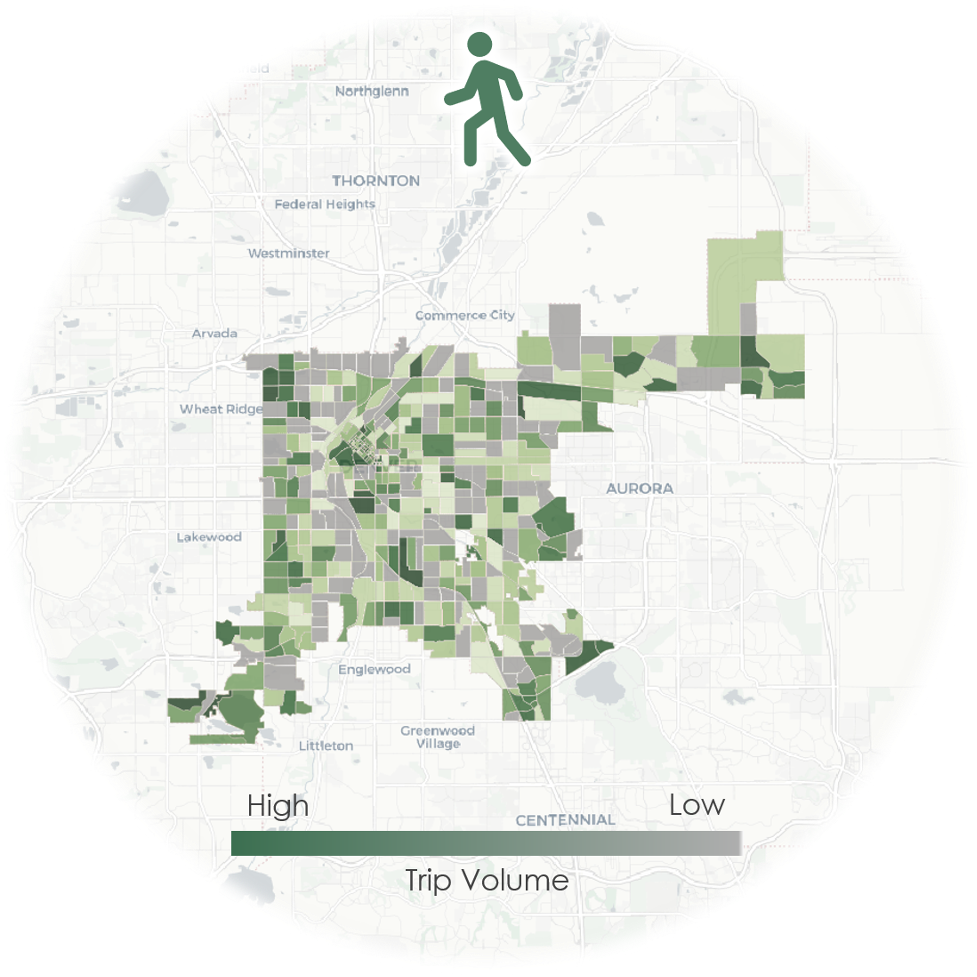

That is exactly where we tried to start with this research. We first wanted to identify what parts of Denver have the most driving trips that – perhaps with better sidewalk infrastructure – could become walking trips.

We also didn’t want to overlook the people that are already out walking in the city – and the sidewalk infrastructure (or lack thereof) that they are using. So in addition to short driving trips, we sought to figure out what parts of the city, particularly outside of downtown, have lots of walking trips.

This combination meant leveraging cell-phone and vehicular GPS-based trip data to figure out where we have lots of short driving or pedestrian trips. We also took population into consideration, since the trip volumes may overlook residents in areas with the same issues but in less populated neighborhoods. In the end, we decided to evaluate 32 areas that had the top short-vehicle and pedestrian trip volumes .

Identifying where Denverites are already making short driving trips or walking is a start, but what do we know about their sidewalks? One approach, akin to the NSRP, would be to send out an inspector. Not a bad idea, especially if you have the time and staff, but we wanted to see if we could narrow thing down even further with some of the amazing data that the Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) has been collecting. Using their planimetric data, we extracted sidewalk characteristics for every street in the entire city. This included figuring out whether the sidewalk exists, and if so, how wide it is. While this data should eventually be used for determining needs across the city, we first wanted to know whether sidewalk availability and/or sidewalk widths were problems in our neighborhoods of interest. This is what we found.

We found a handful of neighborhoods where the sidewalks just aren’t wide enough. We found another few neighborhoods that simply don’t have enough sidewalks. Unfortunately, we also found quite a few neighborhoods with both problems. So if the city wants to improve sidewalk infrastructure, these are all great places to start.

However, we also found some neighborhoods where neither sidewalk width nor availability seems to be the issue. Instead of inspecting every sidewalk in every neighborhood over the course of multiple generations, this is where we should be focusing our inspection efforts. We spent about an hour in each of these neighborhoods and were quickly able to identify major issues with sidewalk cracking, gaps, lips, slopes, and ramps. In the RiNo neighborhood, for example, here are a few examples of what we found:

With sidewalks like these, I can see why so many people are choosing to drive.

Of course, sidewalks aren’t the only concern when it comes to choosing whether to walk or not. And Denver has plenty of other walkability issues related to barriers such as freeways or arterials that feel nearly impossible to cross. Those are issues worth tackling as well, but for now, this simple data-driven methodology can help cities take a more proactive approach to fixing their sidewalk infrastructure and improving ADA accessibility. I for one hate having to worry about which streets have wide enough sidewalks to fit a stroller when I take my kids for a walk.

So before we spend lots of time and money trying to reinvent our cities for a supposed future of self-driving cars and robot-delivery services, let’s get our sidewalks right. Some of these robots need sidewalks too…

[1] The City and Country of Denver currently sets aside about $5M per year for sidewalks. They also say that it will cost approximately $1.1 billion to complete the sidewalk network.

[2] In the full research paper, we also normalized these trips by population to identify a second set of neighborhoods of interest.

[3] The Denver Regional Council of Governments (DRCOG) acquires aerial imagery for Denver and the surrounding region every two years. The imagery is then used as a reference to create a digital representation of the built environment, including sidewalks, also known as planimetric data.