In NYC, the Best Bike Lanes are in Rich Neighborhoods. (But it may not be exactly what you think.)

You don’t have to be a rocket scientist to know that rich neighborhoods have the best bike infrastructure in the city — but it helps if you’re an NYU grad student.

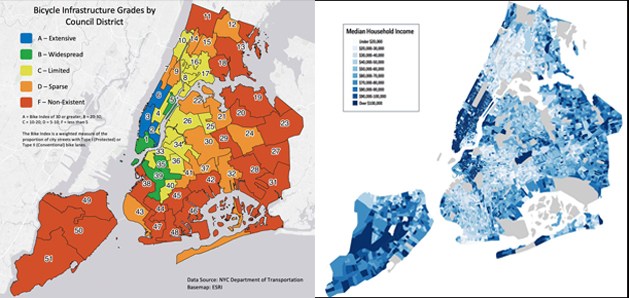

Ryan Morgan, a second year Master of Urban Planning student at the esteemed downtown university and a civil engineer graduate of its uptown counterpart Columbia, blew up the internet on Wednesday by calculating “bike infrastructure grades” (left above) for each of the city’s 51 community districts.

Only three neighborhoods received A grades — and all are in the richest parts of Manhattan (darkest area on the right graphic above).

Only four neighborhoods received B grades — two wealthy neighborhoods in Manhattan and two well-off areas of Brooklyn.

The majority of neighborhoods — 33, in fact — received D or F grades. Many of them are some of the poorest sections of the city.

The graphics reveal anew that the best bike infrastructure is in the richest neighborhoods — but the inverse does not hold true: some of the richest neighborhoods in the city also have what Morgan called “non-existent” bike infrastructure. Eastern Queens, all of Staten Island, and Soundview and Riverdale in the Bronx have household median incomes above the city average, yet all received “F” grades in Morgan’s chart (his methodology is pictured at the bottom of this story).

Receiving an “F” grade does not mean that there’s no bike infrastructure, but merely that zero to 5 percent of road miles in that district feature a protected or painted bike lane (an “A” grade means that 30 to 40 percent of a neighborhood’s roads feature a bike lane). A typical community board district in Eastern Queens has far more miles of roadway than, say, its counterpart on the Upper West Side of Manhattan.

“Of course some wealthier areas in Queens are very sparse on bike lanes,” Morgan told Streetsblog. “[But] in general, I think wealthier residents and high-end real estate developers hold more sway when big decisions about priority investments are being made. That said, many of these areas are in or adjacent to the central business district which justifies a high level of investment to accommodate the high volume of commuters coming in and out every day. We should obviously be investing in bike infrastructure that helps people commute within the CBD, but that’s no excuse for not investing in outlying neighborhoods.”

Obviously, some neighborhoods worry about changes that are billed as “improvements,” he added.

“Opposition to investments based on fears of gentrification is entirely valid in today’s brutal housing climate, but it creates a vicious feedback loop,” Morgan said. “Fewer investments in the transit and bicycling networks reinforces the dominance of car culture and leads to auto dependency [which fuels] an even greater barrier to investments that might take away parking or travel lanes. We need to break the cycle for planned investments to have a chance at success.”

To compile his “grades,” Morgan weighted the results to give a higher letter grade to neighborhoods with more protected bike lanes than standard painted lanes. Other bike infrastructure, such as sharrows, were not counted at all because “they are simply shared routes that involve no separation of bicycle and vehicular traffic,” he said.

Streetsblog created the handy video to show how Morgan’s grading system overlays with the city’s median income in map form (created by Business Insider from census data).

Beyond the issue of basic equity, the most shocking thing about the chart is just how much of the city has F-level bike infrastructure.

The plan specifically calls for “75 miles of both conventional and protected infrastructure in Bicycle Priority Districts,” which are located in parts of Brooklyn and Queens (map right) that not only have mostly bad infrastructure now, but are also some of the poorer sections of the city.

And it’s important to note that when Mayor Bloomberg started building out the bike network in earnest more than a decade ago, officials at the time consciously wanted to start in areas with the most cyclists and the greatest need for the kind of safety and traffic calming that protected bike lanes instill. The city obviously could have chosen to build bike infrastructure on the outer edges and work inward, but it chose to start in the busiest areas — also where it launched Citi Bike — and expand outward.

“Copenhagen wasn’t built in a day, and New York is orders of magnitude larger,” said Jon Orcutt of Bike NY and a former top official in the DOT. “I want an excellent and built-out bike network as much as anyone, but analyses like these mostly show that ‘the city started over here and not over there.'”

But Bay Ridge Council Member Justin Brannan agrees with Morgan that New York’s bike network is a tale of two cities.

“The ‘other’ boroughs are still very much an afterthought,” Brannan told Streetsblog. “We also must consider the clear correlation here when it comes to areas with poor ‘bike infrastructure grades’ and areas that also happen to have abysmal public transportation options — because that nexus is also very real.”

Marco Conner of Transportation Alternatives echoed that sentiment.

“Bike infrastructure is not only about safety for cyclists; it is about providing transportation options in transit deserts, better access to jobs and education for New Yorkers, and safer conditions for all road users,” he said. “New Yorkers are refraining from biking because our streets are designed to be unsafe. Our elected officials cannot wait for more cyclists in their districts to justify more biking infrastructure. We must design and build for the city that we want; and if we want a safe, green and healthy city, we need protected bike infrastructure within and between all neighborhoods. Our city and elected officials are duty-bound to protect all New Yorkers.

Streetsblog reached out to the Department of Transportation for an on-the-record comment and will update this story upon receipt of one.