Creating a Better Place for People to Be Is the Key to a Safe 16th Street Mall

There are certainly reasons why Mayor Michael Hancock, Denver PD, and the Downtown Denver Partnership decided to up security on the 16th Street Mall. Violent criminals, like the man who was filmed rampaging through the 16th Street Mall hitting people with pipes Wednesday, threaten public safety on the mile-plus transit and pedestrian strip.

Targeting criminals makes sense, but there are a few things missing from the conversation around the 16th Street Mall, which lately has revolved around singling out “urban travelers” — an apparent genre of person that Hancock insists does not count as part of “Denver’s homeless” population.

One thing missing is the fact that anyone obeying the law has the right to be on the mall. Another concept not making it into local headlines is that people in public spaces directly reflect the space itself.

“If any one group of people is dominating a place it is a form of privatization,” says Ethan Kent, vice president of Project for Public Spaces. “It is also an indicator that the space is not that interesting or attractive to other groups. Sometimes some tough love is needed, but there also needs to be simultaneous efforts to raise the experience and respect [that] the space gives to everyone, including the people deemed ‘undesirables.'”

City leaders know the mall has unfulfilled potential because they commissioned an 87-page report from Gehl Studios that says as much. Gehl is the same outfit that transformed New York’s Times Square from a car-crushed conflict zone into a people-friendly public space for everyone. The key was to pedestrianize the square — change the place’s nature — to make it a place that people wanted to be.

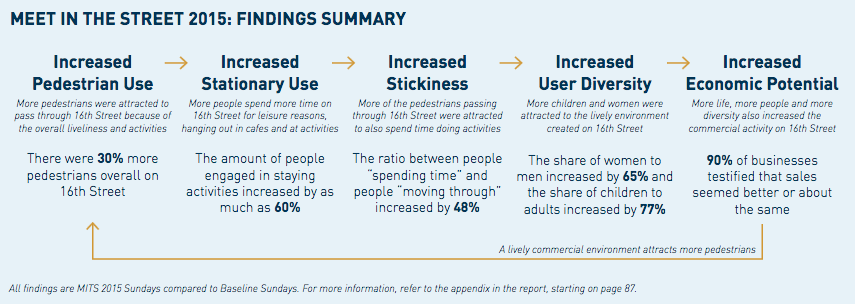

If this idea sounds familiar, that’s because it is the impetus behind the Downtown Denver Partnership’s Meet in the Street events (in their third year), which close the 16th Street Mall to motorized traffic and replace shuttle buses with street furniture and activities. Thirty percent more people flood the mall on these days, and up to 60 percent more people hang out instead of hustle through, according the Gehl report. More people means a safer environment, as well as a more socially diverse one, the report found.

These results are unsurprising and the concepts are not new. Urbanist and journalist William Whyte wrote about them in his 1980 book, The Social Life of Small Urban Spaces. “[‘Undesirables’] are themselves not too much of a problem,” he wrote. “It is the actions taken to combat them that is the problem.” Whyte also said that “the best way to handle the problem of undesirables is to make a place attractive to everyone else.”

In the long run, an army of uniformed police officers and private security guards will not create a place that is simultaneously welcoming, safe, and democratic. It will take changing the place itself (while somehow maintaining the mall’s critical transit service).

“It is amazing how people’s behavior can change when a space respects them, and how people that feel threatening to each other in one space, can feel more comfortable around each other in a better space,” says Kent. “Engaging the various groups in asking how they could make the space better and not make others feel excluded can sometimes be powerful.”