Denver Needs More Than a Train to the Plane to Become a Great Transit City

As exciting as the impending debut of RTD’s A Line to Denver International Airport may be, the hyperbole is getting out of control.

In a Denver Post story exclaiming that the Friday launch of the A line will “change the metro area forever,” DIA CEO Kim Day said her airport is “no longer competing with Dallas and Chicago, but we are now competing with Zurich and Paris and other international airports.” Over at the Denver Business Journal, the downtown-to-the-airport rail connection is an unmistakable sign that Denver is becoming a “true transit city.”

It’s all a bit much. What makes the experience of traveling to “true transit cities” like Zurich and Paris so enjoyable is not just the train from the airport, it’s the robust transit network and walkable streets that enable you to conveniently get around the whole city without the hassle of renting a car. Denver’s not there yet — not even close.

So how much closer does the A Line get us to being a transit city?

Connecting downtown to the airport is important, but to be successful, the A Line should do more than that. As influential transit planner Jarrett Walker put it in a recent post, great airport transit works for airport employees as well as travelers. It should “connect to lots of places, not just downtown” and form “an integral part of the regional transit network.”

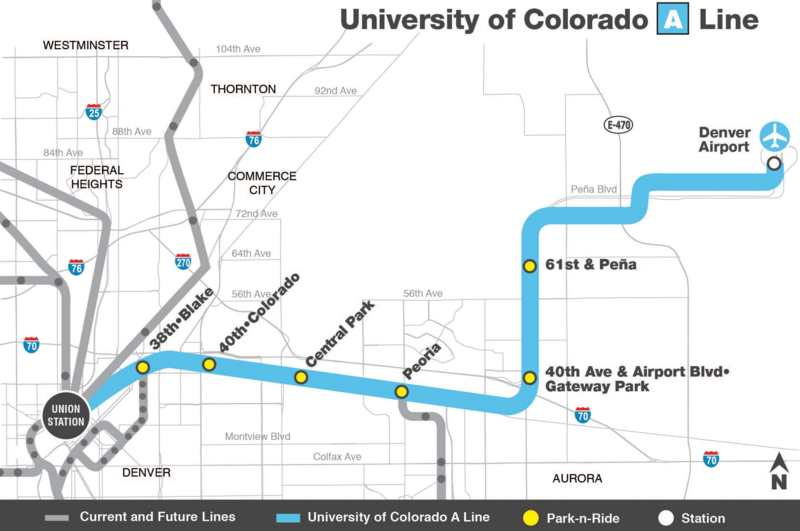

There are basically two things we should be looking for with the A Line. Does it have stations that serve walkable parts of the city with lots of housing or jobs, so it’s useful for many types of trips, not just airport trips? And does it connect with frequent transit routes, so transit riders can access the line even if they don’t live right on top of it?

The R Line will connect to Peoria Station later this year. But while 18 bus lines connect to the six A Line stations between the terminals, only one of those will arrive every 10 minutes or less during rush hour. Nine will arrive every 15 minutes, six will come every 30 minutes, and two will have headways of 30 minutes or more. The 61st and Peña Station won’t have any bus connections.

With the exception of Union Station and to a lesser extent 38th-Blake, the A Line doesn’t serve walkable areas — at least not yet. Take the 40th and Colorado Station. It has some apartment buildings and low-lying businesses around it, but it also straddles an industrial area and a golf course. The Central Park Station is next to sprawling parking lots and a strip mall.

Yes, Community Planning and Development has a Transit-Oriented Development Strategic Plan that aims to make walkable neighborhoods anchored by transit stations, but the unfortunate fact is, the A Line was built for people to drive to. In fact, that’s how RTD has marketed the A Line since day one. Consider:

- The A Line has 4,329 parking spaces (see the giant billboard on I-70 that brags about them).

- According to the FasTracks environmental impact statement, RTD plans to nearly double that number by 2030.

- RTD is marketing their stations as places for air travelers to store private cars for free or on the cheap while away from the city.

Parking spaces don’t come cheap — it costs about $15,000 to build a single structured parking space in Denver [PDF]. RTD is spending tens of millions of dollars on parking for the A Line alone. Those resources aren’t helping to create walkable neighborhoods. Instead, RTD is facilitating car-based development by encouraging people to drive to the train.

Taking the train to and from the airport instead of slogging there on I-70 will be nice. But in many respects the A Line exemplifies Denver’s shortcomings as a transit city. Denver needs a transit system that enables people to make everyday trips without a car, not park-and-ride lots for airport travelers.