What Will It Take to Make Denver B-Cycle More Equitable?

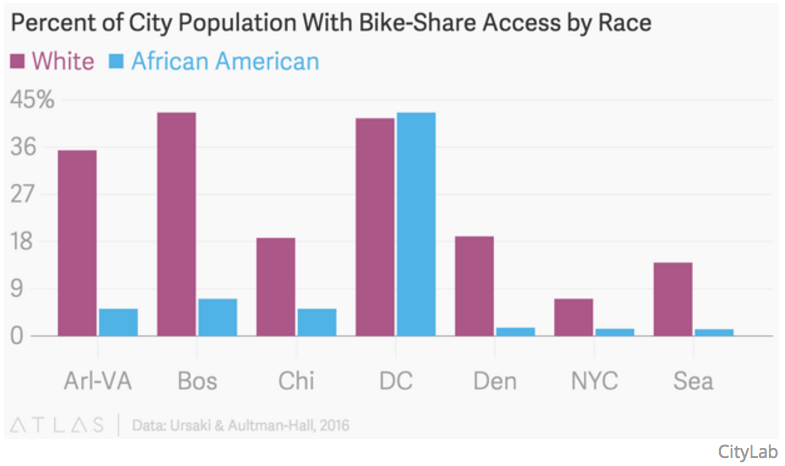

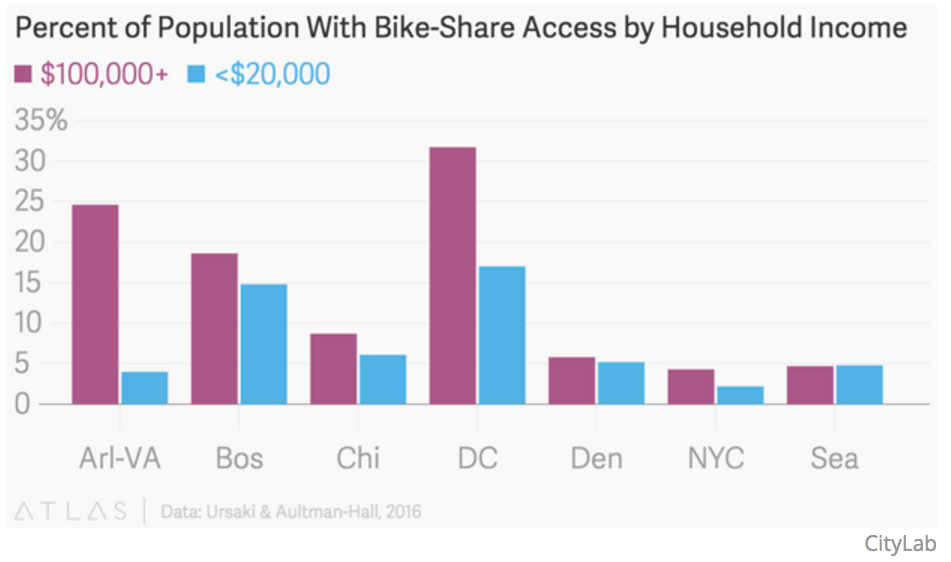

If you’re not white, college-educated, or financially well off, you probably don’t have good access to B-Cycle, Denver’s bike-sharing network. That’s according to a University of Vermont study that found demographic disparities in Denver and other American cities.

As CityLab’s Eric Jaffe reports, the Bikeshare Transit Act might solve the problem by making bike-share organizations eligible for federal funding that’s usually reserved for traditional transit. Problem is, federal money should serve everyone, and most bike-share systems don’t — largely because they have to make money to stay afloat.

Writes Jaffe:

If the bill becomes law it would serve as welcome recognition by federal officials of an increasingly popular urban travel mode. And from a mobility standpoint it’s not a stretch to consider bike-share a complementary part of established bus and rail networks. But the designation raises some flags from an equity standpoint, because to date bike-share systems have done a pretty awful job helping the very populations that rely on transit most: the urban poor.

So does the study ring true? It seems like it. Just look at B-Cycle’s station map and it’s apparent that neighborhoods like Globeville, Elyria Swansea, and Westwood are left out. I spoke with B-Cycle Executive Director Nick Bohnenkamp to get his take.

“To me that study tells us that a lot of people are in the same boat right now,” Bohnenkamp said. “We’re all looking at our funding sources and revenue sources and saying, okay, how do we make this happen?”

In other words, money makes the wheels go round. B-Cycle makes 60 percent of what it costs to operate from members and one-off users. That leaves 40 percent from sponsorships. Bohnenkamp says grants, which B-Cycle receives, are more likely to fund bike-share stations than operation costs — salaries and gas for the trucks that shuffle the bikes evenly throughout the city.

When you build more stations, you create more demand, but B-Cycle isn’t flush enough to keep up with it. “Access is definitely hard,” Bohnenkamp says. “Even if the capital was there and someone said, ‘Here’s a million dollars, put in another X number of stations,’ it’s still a struggle to find operating resources every year to operate it effectively, keep service levels up, and provide that service in the long term.”

B-Cycle offers low-income residents $10 memberships to try to close the gap, but the discount can only go so far if you don’t live, work, or visit areas of the city with bike stations. A $10 pass helps people connect to transit, according to Bohnenkamp. B-Cycle recently extended north into Globeville (39th and Fox) and west into Sun Valley (Decatur-Federal Station), but most of its fleet is in wealthier areas.

This year B-Cycle raised its annual membership price to $135 and closed four stations in South Denver because of poor ridership numbers. But don’t expect those stations to land in low-income neighborhoods. The company is looking to fill holes in the city’s core, which has a lot more destinations than residential neighborhoods, before expanding outward. In a word, density.

“We’re making some changes and trying to optimize our system to make some moves and create that tight, dense network,” Bohnenkamp said. “Probably the most challenging thing — it just boils down to we can only operate what we can financially afford to year after year after year. So somehow if our business model changed or our funding mechanisms change, that would give us perhaps an opportunity to grow a much larger system.”

B-Cycle can’t operate beyond its means, but if it becomes eligible to receive federal transit money, directing that money towards the city’s low-income neighborhoods is a good idea. As Jaffe points out:

A steady flow of federal funding to local bike-share systems might do great things for urban mobility. But it’s a stream that would come with a responsibility to steer the money toward the disadvantaged areas currently missing out on the bike-share party. If these systems don’t serve the public, then it’s hard to see why the public should pay for them—far more fair to let companies putting their brand on the bikes, or the developers charging a premium for adjacent rental units, foot the bill.