CDOT Director Shailen Bhatt on the Agency’s Role in Urban Denver

Colorado Department of Transportation Executive Director Shailen Bhatt has said all the right things since taking over early this year. He talks about his job like he’s looking out for everyone who uses our streets — not just cars and drivers — giving us reason to believe that the titanic government agency will change course and prioritize transit, biking, and walking in its policies.

While CDOT will now be spending 2.5 percent of its budget on bike and pedestrian infrastructure, and has debuted a state-run regional bus service, the department’s commitment to complete streets only runs so deep. Turning around a department as big as CDOT is no small undertaking, and under Bhatt’s watch ill-advised road widening projects continue to move forward.

I recently sat down with Bhatt and asked him to elaborate on his rhetoric and policies. Streetsblog Denver will run the interview in two parts. Here’s the first installment, where we discuss what Bhatt’s agency can do to improve safety on Denver’s deadly urban speedways.

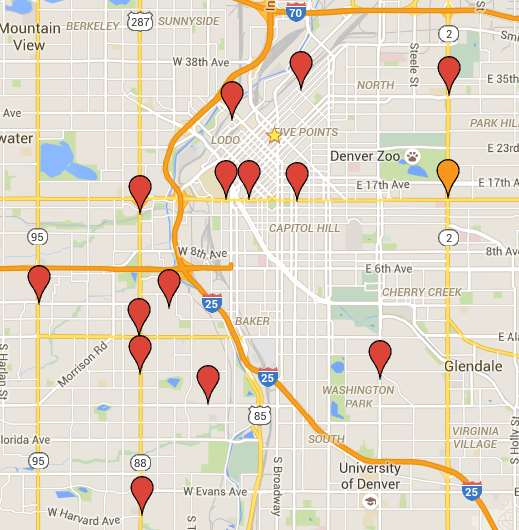

Is it CDOT’s responsibility to keep state highways that are also urban streets, like Colfax Avenue, Hampden Avenue, and Federal Boulevard safe? Is there a plan to protect people walking, biking, and driving on these urban highways?

This is the great struggle. Let’s say we are going to do everything you talk about on your blog. We know that fatalities go up when you get above 35 mph. I also know I wouldn’t take my family biking on Hampden Avenue, no matter how bright a line we paint. Because you’ve got cyclists, and then you’ve got traffic going 50 miles an hour plus. With distracted driving and all that other stuff out there, it isn’t safe. And I struggle sometimes — are we doing it right?

But the other side of that argument is that there are tons of people who depend on these arterials to get places, and so the minute we do something like reduce the speed limit to 35 to make it safe, we’ll reduce the severity of crashes, but also reduce the throughput of the road. You’re gonna create a lot of congestion and we’re gonna have a lot of unhappy people. So I think our role is to look at the NACTO complete street guides to find things. Maybe you can’t do a road diet on Hampden, but maybe you could narrow lanes.

Why not a road diet?

You have such incredible demand. The cars have to go somewhere. This is not casual traffic, these are commuters. And you can create more friction in the system, and then your drive sucks, and all your alternatives suck, so maybe you’ll take transit. I don’t think we can reduce the number of lanes on Hampden without doing a full study of where these people are coming from and what to do in the absence of moving “X” thousands of cars per lane per hour. What I am open to doing is narrowing lanes, so that if people don’t feel like they have this wide open space, they’ll slow down.

So you’re open to doing that, but what’s the next step?

Specific to Hampden, we’ve had a request from a local elected official to have this discussion. Here’s where feelings and gut instinct have to be tempered by engineering. Because anything I want to do, I have to get an engineer to sign his name to it. Now I would argue that we need to do a better job of turning out engineers that have that [federal safety standards] focus. There is an evolution going within DOTs. I’m a different kind of DOT leader that you probably wouldn’t see 30 years ago. It takes time, and we just need to move more of those people up in the ranks and give them more sway and more voice.

But the fact is, more people in Denver die on these urban highways. There’s something about these streets that makes that happen.

Yeah, they’re high traffic, high speed, and bad things happen to pedestrians and cyclists when you have interactions with cars like that.

That’s one way to put it, or you could say that the street isn’t designed for anything but cars and drivers.

And I have engineers who say, “Exactly, and let’s keep those people off of our highways.”

But do you think that?

No, I don’t think that at all. I’m a big believer in complete streets. But it is a big belief in complete streets tempered by the principles that say — the classic example is in Delaware where I was transportation secretary. In Rehoboth Beach, the vast majority of our fatalities were pedestrians at night. And the majority of the fatalities are male, they’re intoxicated, and they come out of an establishment after 10 at night, and they’re not going to walk to a crosswalk. And so they go right across the street and they get hit and they die. And we said, “OK, we’re gonna add 21 new crosswalks here because people are dying.” And the speaker of the house who was from that district said, “Over your dead body will you add those, because you’re going to gum things up for all the roads and all these tourists are going to go to Ocean City, Maryland.

And so we go through this three-year process, and had to have a compromise. We go from 21 to 13 crosswalks. The question is, do you want this to be a road that moves 50,000 vehicles a day, or do you want this to be a street where people can walk? I as a DOT can’t tell you what to do. I don’t think that streets should be highways just for cars, and I don’t think that every urban highway can be a road dieted boulevard with trees and all of the stuff, because quite frankly there are some roads that have to move a lot of vehicles — commercial traffic –that has to get through. I’m saying we have to find that balance and make incremental changes — and support the hell out of communities that want to take a big leap.

Let’s take East Colfax, which the community wants to transform into a complete street. It’s a CDOT street but it’s in Denver, and you’re working with Public Works. How do those conversations go? Which agency takes charge?

I don’t know. In terms of ultimate ownership, Colfax is our road. All of these roads in Denver during peak time are literally these rivers of traffic. Slowing down some of the traffic would greatly benefit the locals. What I have to understand is that there are also people who are using it as a highway — which it is, right now — to get into and out of Denver on a regular basis. One thing that often happens [if you eliminate traffic lanes], is people will divert. And are they then diverting on to local streets?

CDOT has a Complete Streets Policy [PDF]. According to Smart Growth America, the policy scores a 61/100. This policy has been in place since 2009, but CDOT does not track when or how the policy is applied. What will the agency do to ensure that its own policy is being implemented?

I’d like to send that question to our chief engineer rather than speculate on it. I do know that we’ve endorsed the NACTO Complete Streets Guide. We’ve added to the menu of options that our engineers have in terms of solving transportation problems. Historically, if you had a transportation problem, you widened a road — that was the go-to. And now there are other things that are out there like road diets, like bike-ped, like transit. So we are trying to give our transportation engineers some options.

Stay tuned tomorrow for the second part of our interview, where Bhatt discusses the massive I-70 East expansion, CDOT’s role in eliminating traffic deaths, and how the agency can make transit better.