How Can the Denver Region Prevent Displacement Around Transit?

It makes a lot of sense to build walkable development around transit stations. Otherwise, few people will be able to live near transit, and you’ll never have a transit system that enables people to get to work or do their shopping without a car. But as the convenience of good transit access becomes more highly valued, how do you keep rising housing costs from pricing current residents out of their neighborhoods?

More local and state policies to protect tenants would help people stay in place, according to a new report from 9to5 Colorado [PDF]. The problem identified in “Warning: Gentrification in Progress” is that new development is outpacing such policies — if and when decision makers are interested in preserving affordable housing at all.

“These services and amenities, it’s not like we think they shouldn’t be built,” says report co-author Andrea Chriboga-Flor. “I think there just has to be a lot more intentional engagement of residents. Development is coming, and the threat of displacement, so precautions as an afterthought don’t make any sense.”

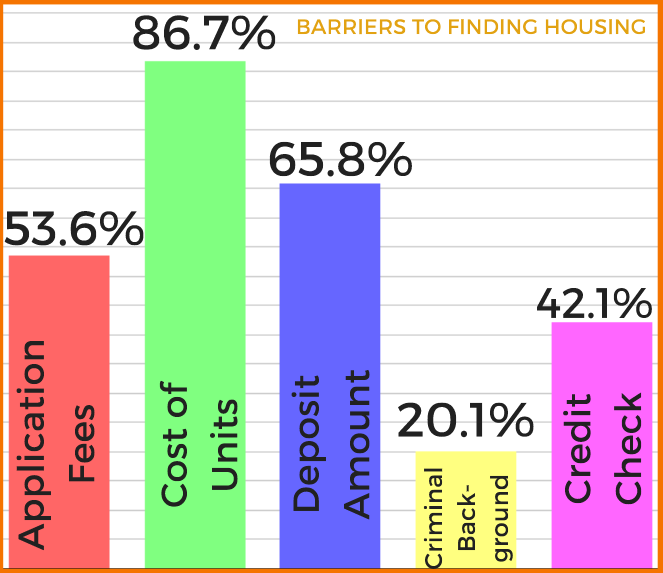

The authors surveyed nearly 1,000 people, with a focus on “low-income residents and residents of color,” for the report. They documented the very real effect that new development can have on Denver-area residents when municipalities don’t address the pressures that lower income residents face in the housing market. Application and deposit fees, for example, can make finding a home prohibitively expensive, Chiriboga-Flor says. Colorado is also the third-most “landlord-friendly” state in the country, the authors find, and tenants don’t always know the rights they do have — or have the resources to fight for them in court.

From the report:

Colorado falls well below the national average for legal aid resources. Without sufficient access to legal aid or renter’s rights education, violations of landlord tenant and fair housing law will continue to go unnoticed.

Yolanda Begay was evicted from her apartment when she could no longer pay her rent. She did not have access to legal aid and was unaware that if she had moved out before the eviction court date, the eviction would not have appeared on her record:

“Even though it would have been really hard to move out in such a short amount of time, not having an eviction on my record would have given me a much better chance at finding housing,” [Begay said]. “I was turned away from transitional housing because of my eviction.”

The report calls on local governments and the state legislature to pass more protections for renters: limiting application costs, making legal aid more accessible, and requiring landlords to show “just cause” before evicting people. The report also calls on localities to subsidize below-market-rate homes.

At the state level, the authors recommend a system of tracking displacement “to better understand what can be done to intervene.” The report also calls for state officials to create a blueprint to make new housing truly affordable for residents who make less than 30 percent of the median income, not just middle-income workers.

The report makes recommendations for residents too: It suggests they create community land trusts — not-for-profit housing co-ops that allow tenants more control than the standard landlord-tenant structure. Residents should also advocate through tenant associations and registered neighborhood organizations.

“We’re not looking for anyone to do this for us,” says Chriboga-Flor. “We want to be part of the process, because right now the process is flawed, because we’re not part of it. And a lot of the polices [local governments] pass don’t meet the needs of the people actually live in these places. We know this is a huge push. We know this is against everything that’s happening. So we know we need a movement.”