When Denver Added Bike Lanes to Larimer Street, Retail Sales Skyrocketed

When cities try to carve out more space for walking or biking in lieu of car traffic or parking spots, retail business owners often worry they’ll lose revenue. But a new study by University of Denver grad student Stephen Rijo shows there’s nothing to fear [PDF]. In fact, retailers should probably rejoice when their street gets redesigned.

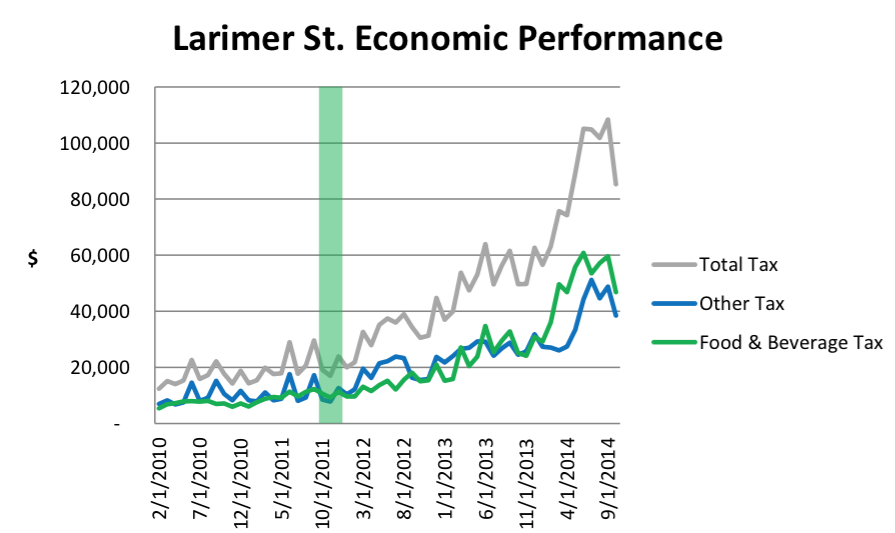

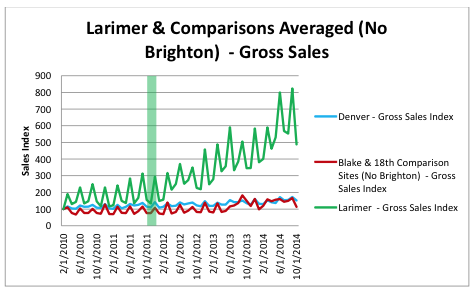

Rijo studied two streets with relatively new bike infrastructure — Larimer and 15th — and measured their retail performance against similar streets that were not redesigned. Sales tax intake rose in both cases — with an especially dramatic increase on Larimer Street.

“Decision makers like numbers that they can just point to, so I think that was a large piece of why we needed to have some solid number piece, dollar signs, ideally, for the economic impact,” Rijo said.

Rijo cautions that the 15th Street bike lane, which was installed in 2014, needs to be around longer before there’s sufficient data to draw hard conclusions from. A one-mile stretch of Larimer Street between Broadway and Downing, on the other hand, was converted from a one-way, two-lane street with no bike lanes into a two-way street with one car lane and a bike lane in each direction. That was back in 2011. With more than 18 months of data both before and after the redesign, you can see the change in retail sales.

With Denver struggling to fund bike infrastructure, Rijo’s research is important to keep in mind. It suggests that the expense of building bike lanes could pay off in the form of a more robust tax base.

Here’s a look at sales tax collections on Larimer Street before and after the redesign (represented by the green bar):

And here’s how Larimer compared to Denver as a whole, as well as to streets with similar retail characteristics. (Data was collected for Brighton but discarded because some businesses changed the way they reported taxes midway through the study.)

Rijo concludes that “bicycle facilities are correlated with statistically significant positive economic impacts for local businesses and do not have negative impacts.” In other words, Larimer is just one street, and the study doesn’t prove that street redesigns are causing the increased sales — other factors could be at work — but there’s no basis for merchants to worry that reducing speeding and providing safe space for biking will hurt their bottom line.

“I heard a business owner say once, ‘When I bought this real estate, I had an agent telling me that 30,000 cars pass this spot each day,'” Rijo said. “That’s 30,000 cars that are passing you at 35 miles an hour, in a hurry to get out of the city. Whereas if you make that an appealing place for cyclists, they’re passing at 10 or 15 miles an hour, and are more likely to stop and buy something and make those non-essential stops.”

Rijo could be describing any number of Denver’s streets. But Broadway, which funnels drivers out of the city and creates havoc for people walking and biking, comes to mind. Protected bike lanes are possible on the important north-south connection — “the Spine of Denver” — but progress is slow going. Based on his findings, Rijo is confident that bike infrastructure would enhance commerce and livability on a street like Broadway — for cheap.

“It’s just one of those places where it’s a common sense, really cost-effective thing to repurpose a little bit of street space for cyclists,” he said.