Denver’s Buses and Trains Are Not Useful to Most People. A New Book Shows Why.

Denver built a transit network that most people don’t use. It doesn’t go where they want to go. Trips take too long. And the primary hub, Union Station, is three-quarters of a mile from the heart of downtown’s job center.

The region’s public transit does some things well. But it often fails to get the basics right according to the urban planner Christof Spieler, author of the new book “Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of U.S. Transit.” ($40, Tattered Cover, Island Press.)

The book, which looks at public transportation systems across America, starts with a quick discussion about the essential but often neglected features that make transit successful. What follows in most of its 264 pages is a fascinating atlas that profiles 47 transit systems, including Denver’s Regional Transportation District. For each city, photos, maps and infographics complement easy-to-follow writing, illustrating what each city gets right — and where they fail.

In a recent interview, Spieler shared his thoughts about Denver. Andy Bosselman conducted and condensed the interview.

A: When we talk about transit, we should always measure it in terms of how useful it is to riders. First of all, does it go where they’re trying to go? Does it go there frequently, so they won’t have to plan their lives around it? Does it run long enough, so that it’s there for them when they work late?

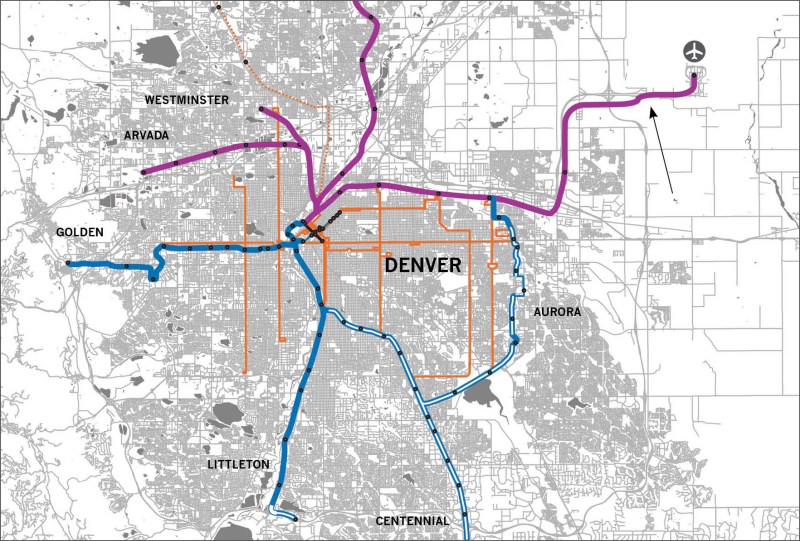

Q: In the book, you mentioned that Denver’s regional light rail system doesn’t serve the city of Denver well. It doesn’t go to the densest neighborhoods. It doesn’t go to the main hospitals, shopping districts or cultural institutions like the museums.

A: In Denver, the light rail system is focused on serving suburban-downtown trips. It generally provides a really good level of service, a really good level of reliability and a really good level of amenities. The question is simply, does it go to the places where people want to go?

Q: Where light rail does go, you say the stops often are not located in places that are useful to people.

A: You have things like the [Anschutz] medical center and the Tech Center, which are real activity centers. If you serve those well, they can get you a lot of potential ridership. Both have light rail kind of near them, but not in the middle of them.

[At the Anschutz Medical Center] there is a light rail station off to one edge. But if you actually map things out, much of that campus really isn’t within a reasonable walk.

The Tech Center is a very similar situation, where there is light rail. But it’s on the opposite side of the freeway. If you want to get any of those jobs, some of them are really outside walking distance. But even the ones that aren’t, the first part of your trip is walking across this giant concrete moat.

Q: Those seem like very basic mistakes. Where did Denver go wrong?

A: A lot of those are decisions are political. It may well be that RTD actually wanted to get to get this transit right into the middle of things and they got pushback.

When you put transit into the middle of things, it has impacts. There may be fewer places to turn left. There is going to be construction when it gets built. Those businesses, those residents are going to be concerned.

What you see often is the decision makers [saying to themselves], ‘You know this is too hard. We’re just going to go for the easy path that doesn’t have resistance.’

If you are building a transit line and nobody is against it, it’s probably a bad project. Because it means you’re not going where it actually affects anybody. You’re going where nobody wants to go.

Q: And Union Station isn’t exactly where most people want to go.

A: In terms of making a really amazing place out of what was largely dead, Union Station is amazing. As a development, it is extraordinary. But as a transit idea, it doesn’t seem nearly as strong.

The biggest hole is the idea of Union Station as a transfer hub on the edge of downtown. A large part of the light rail lines and all the commuter rail lines don’t actually go into downtown. They stop on the edge of downtown. Then you need to get off and get onto the [Free Mall Ride], which makes all of those trips less convenient and all of those trips slower.

Imagine something where the Mall Ride is actually converted to light rail. And light rail trains go right through the middle of downtown and serve the same Mall Ride function they do today. But they are also a continuation of [each] line. [Unfortunately] that would be a big change to infrastructure that was just built.

Q: Should I imagine rail on Colfax, too?

A: The Colfax corridor has higher ridership than any of the individual commuter rail lines. Yet it is still a local bus in mixed traffic. [The planned Bus Rapid Transit line for the corridor] is a really good project and will be a vast improvement.

If you look at the advantages of rail over BRT, rail has a higher capacity. And when you have rail lines that are much lower ridership than that BRT line, you can definitely ask the question: Shouldn’t that have been rail?

Q: Your book brings up how race and class factor into decisions about where to put bus and rail lines.

A: There is no place in the United States where race and class aren’t somewhere beneath the surface — and often quite explicit in the planning discussions. That’s something we need to really be serious about.

In Denver, suburban-downtown trips, which are fundamentally what the Denver light rail system is focused on, that’s based on a mental model of who you are trying to attract.

There are a lot of cities that frame their transit discussion around the idea of choice riders versus dependent riders. You essentially say, ‘we operate our bus network because there are these transit-dependent riders that we need to serve. And now we’re going to build a rail line for the choice riders who we are trying to get out of their cars.’

In calling somebody a transit-dependent rider, you’re essentially dismissing them. You’re essentially thinking of them as somebody who has no choice but to ride our system, which means there’s no argument for making the system any better for them.

One of the things we really focused on in Houston was saying we want to improve our bus network so that people who are already riding this system have better trips.

Q: You are known in transit circles for helping Houston Metro redesign its network of bus routes. Your focus on getting essential elements right helped the redesign grow ridership at a time when many cities, including Denver, have seen fewer people taking transit. You say that Denver has some room for improvement.

A: If you look at where Denver has its frequent [but] service, it correlates pretty well to the population density. It goes to where people want to go.

But on the local bus network, you have much less reliable service. You have much lower-quality stop amenities. That transit, even though it goes where a lot of people want to go, is generally lower quality and thus less useful to people.

One of the things that Houston does is think of the light rail network and the bus network as one single network. Other cities, too, really see the [two] as working together, as part of one system. And that feels like an opportunity Denver has not taken.

I focused on criticisms, but are there some things Denver gets right that we didn’t cover?

There is no other commuter rail line in the entire United States which is frequent as the A-Line in Denver. Which is humorous, it literally runs through open prairie. And the dense suburbs of New York have much worse service.

The Denver fare system [which integrates commuter, regional and local trips into a single fare] is actually working in the right direction. It’s a big deal and something that a lot of U.S. cities would benefit from doing.

“Trains, Buses, People: An Opinionated Atlas of U.S. Transit.” ($40, Tattered Cover, Island Press.)

Streetsblog is free to all. But we can’t do it without you. Give $5 per month.