Denver’s 5280 Loop Could Be a Car-Free, Health-Forward Oasis that Gives Public Streets Back to People

Remember the linear park that supplanted a previously lifeless block of 21st Street for two months this summer? The city closed the street to cars, added a bunch of trees and seating, and created a vibrant place for people walking, biking, playing, and shopping.

What if five miles of city streets looked more like that and less like a racetrack for cars? That’s what the 5280 Loop would do, linking the city’s neighborhoods and creating a healthier environment in the process. The Downtown Denver Partnership is leading the urban trail’s development, but “the city has been a part of this every step of the way,” said Adam Perkins, an urban planner with the Partnership.

Transportation planners are aiming high: The urban trail would repurpose whole streets currently reserved for cars and retrofit them to prioritize people. That could mean completely car-free streets on some segments, or woonerfs — streets where cars play second fiddle to people walking and biking, like the idea floated for Wynkoop Street.

“Let’s imagine the best thing,” said Chris Parezo, a planner with Civitas, a local firm consulting on the project. “Let’s not be limited by today’s status quo.”

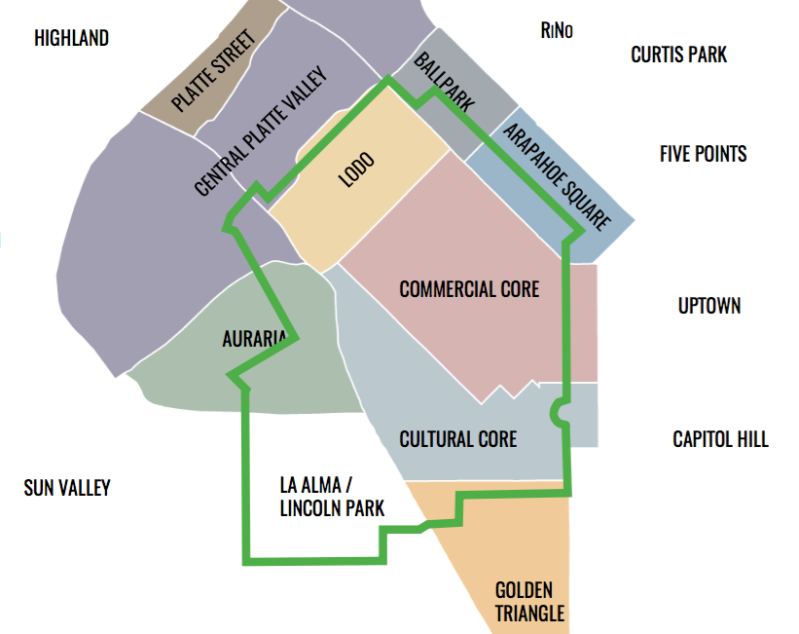

Parezo spoke at a community meeting in Capitol Hill last week, where residents mocked-up huge maps with ideas for the still-conceptual route. As of now, the urban trail would weave through distinct areas of the city: from the government seat of Colorado around the Capitol to the museums of Golden Triangle, to La Alma, Auraria Campus, Union Station and Coors Field.

“We have this thread stringing together these very different, unique areas,” Parezo said. “And I just want to emphasize that, because that’s why we think it’s important to sort of build this up from each neighborhood.”

Here’s the plan as of now.

Cars dominate Denver streets, but it hasn’t always been that way. The 5280 Loop would give more space to people walking and biking in an urban environment that typically pushes them to the margins.

Thirty-five percent of the space within a quarter-mile of the 5280 Loop belongs to the public, according to a Downtown Denver Partnership presentation. Three percent of it is parkland and 32 percent of it is public right-of-way — streets. The majority of that street space, though, is for driving and parking. The Loop would change that.

“We wanted to start changing people’s thinking to where the street is more about peds and bicycles, commerce, people, and less about the car,” Parezo said.

A healthier built environment

The idea is “to build a more livable city,” Perkins said. He means that literally.

Streets dominated by cars are bad for public health, whether it’s the pollution that cuts through the human respiratory system or the traffic deaths and injuries caused by a system that values speed over human life. Planners want the Loop to improve public health in a way that’s meaningful and measurable.

The Partnership is contracting with HealthxDesign, a public health studio that uses the built environment to create physically healthier places. Planners will develop indicators for health and ailments and weave elements into the Loop aimed at improving health outcomes.

Take downtown Denver’s sparse tree canopy, for example. More trees could not only generate cleaner air, but might curb obesity rates by creating more pleasant places to walk, either for transportation or recreation, Parezo said.

“Fifteen to 20 Years, but not 50”

The 5280 Loop’s current setup has a circumference of five miles and crosses about 52 intersections. That’s a lot of retrofitting in a city where building a protected bike lane can take years. It’s too early for anything other than an estimate, but Parezo said the Loop’s completion could be in “15 to 20 years, but not 50.”

Funding is also a question mark for the Loop. Mayor Michael Hancock allocated almost $1 million to continue the design process in his 2018 budget, but the project could cost $100 million. The funding will shape up eventually, once everyone knows precisely what will be funded, Perkins said.