Subways and Pods: A History of Denver Transit and Why We Shouldn’t Obsess Over Tech

What if, instead of light rail cars clanging alongside downtown traffic, Denver’s trains burrowed underground? Or if, instead of trains, Denver had a network of tracks elevated on stilts throughout the city that flung personal pods from neighborhood to neighborhood like a kid’s slot car racetrack?

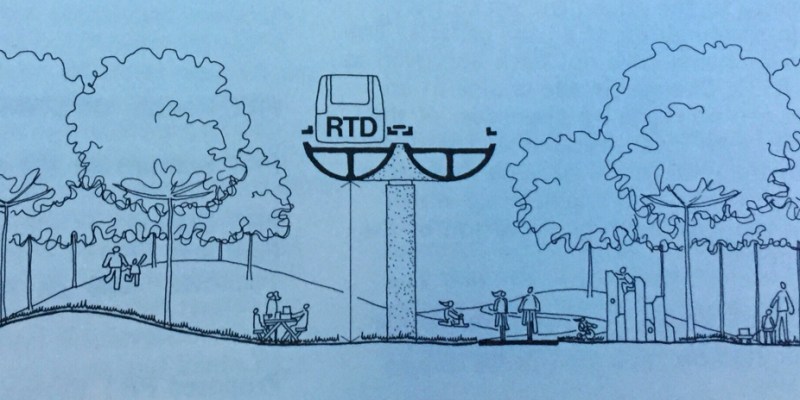

At one point in Denver’s history, these were serious alternatives to the transit system we know today. The Regional Transportation District (RTD) and city officials flirted with this Jetsons-esque technology — a “personal rapid transit” (PRT) system — in the 1970s. When that didn’t pan out, the agency considered building a subway downtown.

“You’d just press the button for where you want to go, and you’d have a nonstop trip,” says Bill Van Meter, RTD assistant general manager of planning. In the 1990s, Van Meter authored a history of RTD’s fits and starts, including PRT, which the agency considered in 1972.

Unlike buses and trains, these pods could carry no more than 20 people at a time. They would have shuttled you directly to one of 40 or so stations, without stopping, along a 98-mile network high above Colorado Boulevard, Colfax Avenue, Sheridan Boulevard, Santa Fe Drive, Hampden Avenue, I-25, U.S. 36 and other corridors. Automated and driverless, many thought the system would have been an alluring technological coup for Denver at the time.

Would have. Maybe. It turns out building a futuristic transit system resembling a really boring roller coaster was expensive. RTD officials estimated the cost at about $1.6 billion in 1972 dollars, a budget that would have also covered a complementary bus system. That’s about $9.2 billion today. The city needed help from the feds, and the Urban Mass Transit Administration was willing. After all, Denver was about to host the 1976 Olympics. PRT would’ve been the perfect way to shuttle Dorothy Hamill around the city.

But that didn’t happen. Colorado voters shunned the Olympics, and, with it, personal rapid transit.

“The demise really was the fact that the region voted down the Olympics,” Van Meter said. “UMTA then said, ‘Well, no Olympics, no reason for us to fund you guys.'”

That’s probably not the worst thing to ever happen. The technology never developed well enough to get beyond fad status. There’s a reason public PRT systems barely exist today: It could have easily been a money pit for Denver, says Van Meter. Besides, transit works because it moves a lot of people using a little bit of space. It’s as if RTD thought PRT would give Denverites an experience more akin to the automobile — a chance to somehow meld western independence with mass transit. RTD chose pods over trains because they offered “highly personalized service,” a 1973 RTD transportation plan stated.

To this day, Morgantown, West Virginia, is the only American city with a public PRT system, and it’s small. “Ours was going to be pretty massive and complex,” Van Meter said.

Flirting With a Subway

In 1976, city leaders and RTD knew Denver needed a “rapid transit system” — a transit service on a fixed guideway that was as convenient as driving, if not more, and carried a substantial amount of people. They considered adding a subway as part of a broader, above-ground light rail service, but again would need help from the feds.

Planners envisioned a light rail subway throughout the central business district, with the main lines along 16th and California Streets, according to technical drawings from the late 1970s. Trains would have burrowed under West Colfax for a stint and jogged south before coming up for air on the southwestern edge of downtown. A train would have ran under Broadway as well, though it would have gone aerial, along an elevated platform, at around 22nd Street. Portions of either East Colfax or 16th Avenue would have housed a subway station to connect people with the Colorado State Capitol.

Obviously, it didn’t happen. Denver was too car-oriented and sprawling to win federal funding over other cities, UMTA decided. “Rail transit was thought to be ‘premature’ for a region with such high automobile use, low population density, and low transit ridership,” Van Meter wrote in his history of RTD.

The feds awarded $650 million to Detroit instead, in “a move many people felt was calculated to bolster the reelection effort of former President Gerald Ford,” a 1980 Denver Downtowner article claimed. UMTA gave Denver $200 million for its bus system, and the city would not see rail until the ’90s.

What If?

But imagine if the MallRide shuttled people underground between Union Station and Civic Center Station, or if the light rail didn’t have to mingle with cars on California Street downtown. How would Denver be different?

Kathleen Osher, executive director of Transit Alliance, thinks the redevelopment of Denver’s historic buildings — its Lower Downtown warehouses and even Union Station — and the walkable, dense downtown that they anchor, may never have happened if an underground train came along at that particular time in Denver’s history.

“I think that it would have been possible and easy to conceive that that type of infrastructure investment would’ve said, you know what? No. Denver is a modern city, we’re gonna get rid of all this old stuff, and we’re thinking only new stuff from now on,” Osher says. “I don’t know that LoDo would’ve ever become that walkable place at that point in time.”

Transit done well doesn’t just move people; it creates walkable communities where people dominate the streets, not cars. Stations usually anchor those places, with compact housing and commercial space creating tight-knit neighborhoods.

The 16th Street MallRide is frequent, but not particularly fast, stopping every block between Civic Center Station and Union Station. A subway would carry more people through downtown, and would be faster, unimpeded by cars and traffic signals. While that may have been good for commuters trying to flood the city in the morning and flee it in the afternoon, it might not have been great for street life on the Mall, says Van Meter.

“In my mind, the 16th Street Mall, just because of the accessibility and visibility it provides, is more supportive of commercial and higher density land use than a subway would’ve been,” Van Meter says. “The vertical circulation of going up and down [to get to the subway], doesn’t engender me thinking at lunch time that I want to go to Walgreens and buy something or I want to go part way down the mall for lunch.”

But off of the Mall, a subway could have supported more people living and working downtown earlier on, long before the more recent downtown renaissance. The light rail on California Street, for example, is constrained by traffic and can’t carry more than four cars worth of people downtown. “Presuming it was actually providing access to and from both city and suburban origins and destinations, I can imagine much higher density land uses being supported because the capacity would’ve been higher,” says Van Meter.

If RTD had built a subway instead of at-grade rail region-wide, there might be a lot more room for walkable, people-first places, says Wesley Marshall, an urban planning and civil engineer professor at University of Colorado Denver. Instead, park-and-rides create craters around most of Denver’s rail stations outside of the central business district.

Marshall illustrated his point with Alexandria and Arlington, two Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. Back in the ’70s, Arlington opted to pay the extra money to put its Metro lines underground, but Alexandria didn’t.

“With their bullseye zoning approach, Arlington became the poster child for good transit-oriented development in this country,” says Marshall. “On the other hand, Alexandria created a bunch of park-and-rides. Because they weren’t dedicating as much land to transportation and parking, Arlington now gets like 70 percent of their tax revenue from 30 percent of their land around those underground stations. I’m guessing that isn’t the case in Alexandria because there just isn’t room for such development. Moreover, Alexandria has found it to be pretty difficult to change the character of these stations to something resembling a real TOD.”

The Next Chapter

This stuff isn’t just fun to imagine. It’s relevant today, as Denver looks to once again overhaul its transit system, this time through the Denveright planning process. Rather than obsess over technology, Denver needs to first establish its values — what it wants out of transit — then find the best way to get there, says Osher, who heads the transit plan task force. One of those values will be the freedom to live a convenient life without owning a car.

“I don’t think it serves us well as a community to have a discussion about specific technologies,” she says. “There’s a lot of merit for us to talk about the functionality, and really grow out of this mentality that transit . . . is all about commuting. I think it really becomes about that mobility and movement in your life.”

While automated vehicles and driverless cars dominate the conversation about the future of transportation, any city planner will tell you that the geometry of cities doesn’t allow for each and every person to own her personal vehicle these days. That’s especially true in rapidly growing cities like Denver — a place where many people used to move solely to be close to mountains.

“I always say that the reason I love transit is because we have to get out and experience each other’s lives,” says Osher. “You have to get out and be part of this city, instead of living in your metal bubble that takes you in and out of the city just for work.”

People want “to be part of an urban fabric, and I hear an understanding that this brand that we’ve built around quality of life feels more tangible here than in other parts of the country,” she adds. “And I don’t think that we need any specific technology to do that.”