Denver’s Sidewalk Policy Is Designed to Fail, But That May Be Changing

It’s safe to say that Denver City Council members cannot plead ignorance on the city’s embarrassing walking infrastructure, following a meeting Wednesday where reps from Denver Public Works briefed lawmakers on the state of the city’s sidewalks.

It was the first gathering of the Sidewalk Working Group, a committee led by Councilman Paul Kashmann and formed at the urging of advocates including WalkDenver. Entrenched in policies from the 1950s, Denver has long viewed sidewalks as frills. The committee aims to form a policy that ensures legitimate sidewalks for all in a city where their construction and maintenance usually depends on property owners.

“Our point is that we should look at sidewalks as part of public infrastructure,” said WalkDenver Executive Director Gosia Kung. “There’s no difference between a street for vehicles and a sidewalk for pedestrians. We don’t expect people to fix a pothole in front of their house. If there’s a pothole, the city takes care of it. So we should look at sidewalks the same way, as a part of the transportation network that’s a responsibility of the city.”

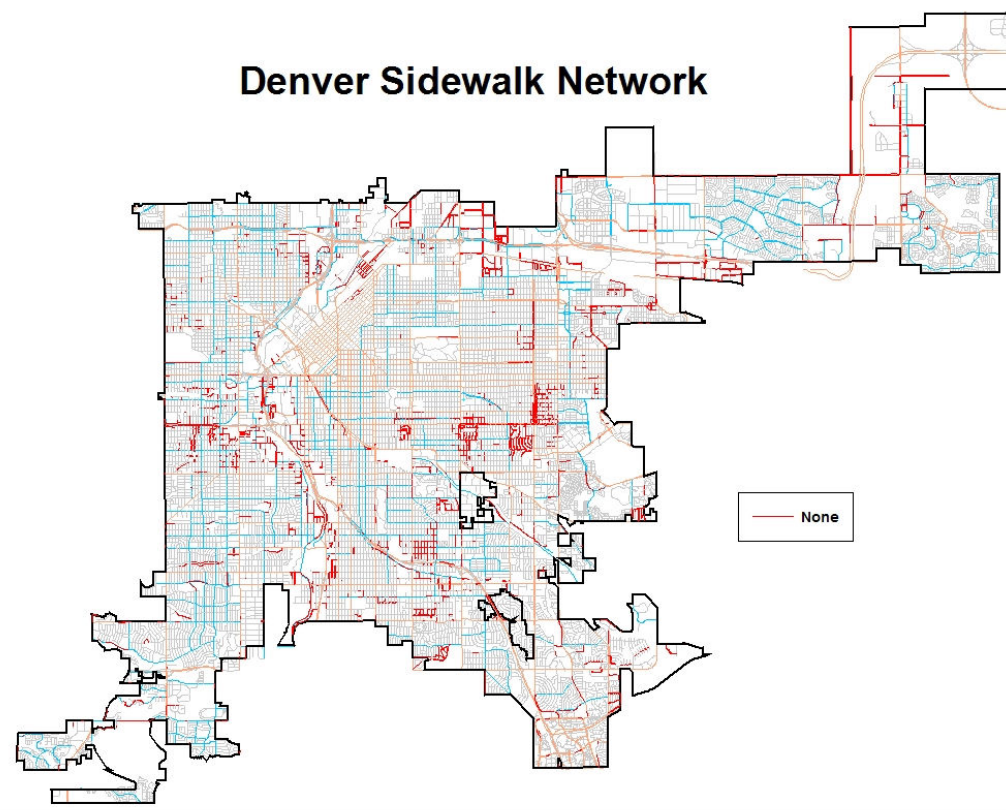

About 250 miles of streets simply don’t have sidewalks, according to Public Works. Reps told council the city had 3,145 miles of sidewalks, but didn’t drill down into how many miles of pavement were shoddy or less than the standard 5-foot width.

The current policy is a recipe for un-walkable streets. For instance, it requires homeowners in poor neighborhoods, where walking infrastructure is worst, to pay thousands of dollars to fix the public right of way. And even if residents can afford to fix a sidewalk, enforcement doesn’t work. It’s complaint-based, but the city only allots one sidewalk complaint per resident per year. (A contractor trying to drum up work made more than 200 complaints so the city shut off the faucet for everyone.) Public Works cited just 16 residents last year.

“We do cite for deficiencies but it is rare because it is very intrusive,” said Rob Duncanson, an engineer with Public Works. “It can be very expensive to require a citizen to go fix the walk on a corner lot. It is not a common practice just to go out and look for those kinds of situations.”

The system is also designed to shield Denver from getting sued. If the city took responsibility for sidewalks, it would open itself up to lawsuits based on the Americans With Disabilities Act and pretty much anyone hurt or killed while walking. Case in point: Since 2010, the city has been sued nine times for shoddy sidewalks. It only lost twice and paid a total of about $5,100.

So what you have is a policy that requires individuals to spend their own money to fix public property, but if people can’t or won’t, there isn’t any recourse. On top of that, federal law doesn’t require Denver to do anything about it.

“Right now under our existing system, by our Denver code, the abutting property owners are obligated to maintain existing sidewalks,” said Mitch Baier, of the City Attorney’s Office. “Under that system the ADA does not currently require the city to maintain the sidewalks up to ADA standards. Similarly, under our existing system, the ADA does not require the city to install new sidewalks up to ADA standards.”

For their part, most of the 10 City Council members present expressed surprise over how something so basic has fallen through the cracks for so long. “From what I’ve heard, we’re saddled with a lot of policies and decisions that were made 50, 60, 70 years ago,” said Councilman Kevin Flynn. Councilman Rafael Espinoza cautioned that the many mobility plans Public Works has on the drawing board are great, but that “longstanding needs are self-evident.” In other words, it doesn’t take rocket scientist to know sidewalks are necessary.

At the same time, a City Council staffer wrote a white paper that essentially says Denver’s approach to sidewalks is in line with other cities — even though our suburbs do a better job.

So what will a solution look like? It’s unclear. In the short-term council members see low-hanging fruit where sidewalks are cruddy or non-existent on city-owned properties. But that’s a piecemeal approach. WalkDenver and Mile High Connects researched several long-term solutions — a fee, a ballot measure, or a more creative approach that bases liability on foot traffic, for example. It doesn’t matter, as long is it’s comprehensive, said Kung.

“It’s great to see the interest,” she said. “I think the discussion is early and [council members] are all kind of focused on their districts. And I hope that they’ll get there, to understand that it’s really a citywide issue — a policy issue as opposed to an incremental change.”