Denver Can Have Great Neighborhood Streets If CDOT Tears Down I-70

Unite North Metro Denver has an idea about what to do with I-70. Instead of widening the highway and pumping more traffic into the city like Colorado DOT wants, tear it down and replace it with an urban boulevard, reconnecting the urban fabric of Globeville, Elyria, and Swansea.

CDOT is pushing its billion-dollar-plus plan to reconstruct and widen I-70 and insists a boulevard solution would somehow cost more than a new, grade-separated highway structure.

Now UNMD has a visualization to counter the pretty renderings and videos that CDOT’s been putting out for more than a decade. This video envisions walkable, bikeable neighborhoods along the I-70 corridor without the pollution, noise, and physical barriers created by the highway.

Tearing down highways and restoring the city street grid sounds counterintuitive — it’s natural to wonder what happens to all that traffic. But plenty of precedents have proven that cities can thrive by removing heavily traveled urban highways.

When San Francisco’s Embarcadero Freeway, New York’s West Side Highway, Milwaukee’s Park East Freeway, and Seoul’s Cheonggye Freeway came down, the much-feared traffic nightmare never materialized. In each case, people chose other routes, consolidated trips, shifted to off-peak times, or traveled by other modes. The street grid — where a lot of highway traffic ends up even when the structure is still standing — was more than up to the task of distributing the traffic that remained.

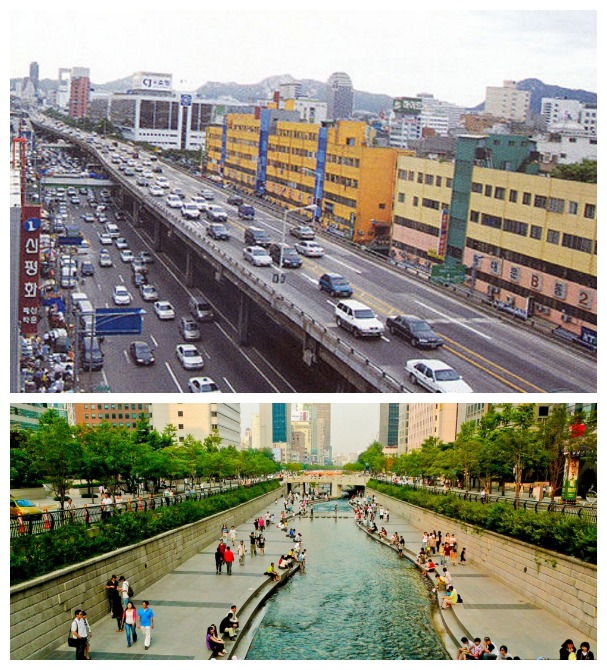

The Cheonggye Freeway is probably the most dramatic illustration of a city removing a highly-trafficked elevated road. As Seoul urbanized, the city’s expressways became more congested than ever. Instead of making more room for single-occupancy vehicles to handle that growth, the government tore done the highway, replaced it with surface streets and a park, and invested in transit. Today the downtown is booming, thanks to Mayor Lee Myung-bak’s vision. He led the charge to tear down 15 more expressways and rode his success all the way to South Korea’s presidency in 2008.

After San Francisco’s Embarcadero highway was damaged in a 1989 earthquake, city leaders had the foresight to replace it with a surface street instead of rebuilding a hulking concrete barrier to the water. It cost $20 million less than the rebuild and sparked a renaissance on the waterfront. Neighborhoods that had withered next to the highway began to attract new housing and jobs, and formerly wasted space by the water was reinvented as tourist destinations.

The grandaddy of them all might be New York’s West Side Highway. When a portion of highway started to collapse in 1973, rendering it unusable, transportation planners were surprised to observe that a significant chunk of traffic simply disappeared as drivers chose different ways to get around. Eventually, the highway was replaced by a surface road, known as West Street, and Hudson River Park. The waterfront greenway that runs through the park is now the most heavily biked route in the United States, with several thousand cyclists using it each day.

The point is, tearing down highways can have a dramatically positive effect on a city’s economy, health, and wellbeing. Just because Colorado DOT has worked to widen I-70 for 13 years doesn’t make it a good idea. Mayor Michael Hancock and Colorado DOT Director Shailen Bhatt can either sit back and open the floodgates to more traffic, or they can lead on this issue and change the direction of Denver’s future.

Hat tips to Dean Foreman, Constanze Arenz-Kulkarni, and Keith Billick.